I like direct clear-spoken people, so you can see why Native American names appeal to me. “Head-smashed-in-buffalo jump” was just that — a place buffalo were chased off a cliff and killed for food. (An alternative legend has the place’s name originating from a careless young warrior at the jump’s base who had his noggin smashed in by the half ton mass of a falling bison).

Located 18 km northwest of Fort Macleod, Alberta, where the foothills of the Rocky Mountains meet the great plains, is one of the world’s oldest, largest, and best preserved buffalo jumps. Head-Smashed-In has been a communal hunting site used by aboriginal peoples for almost 6,000 years (until abandoned in the era of horses and guns). It provides a direct link to prehistoric life in North America and has been recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

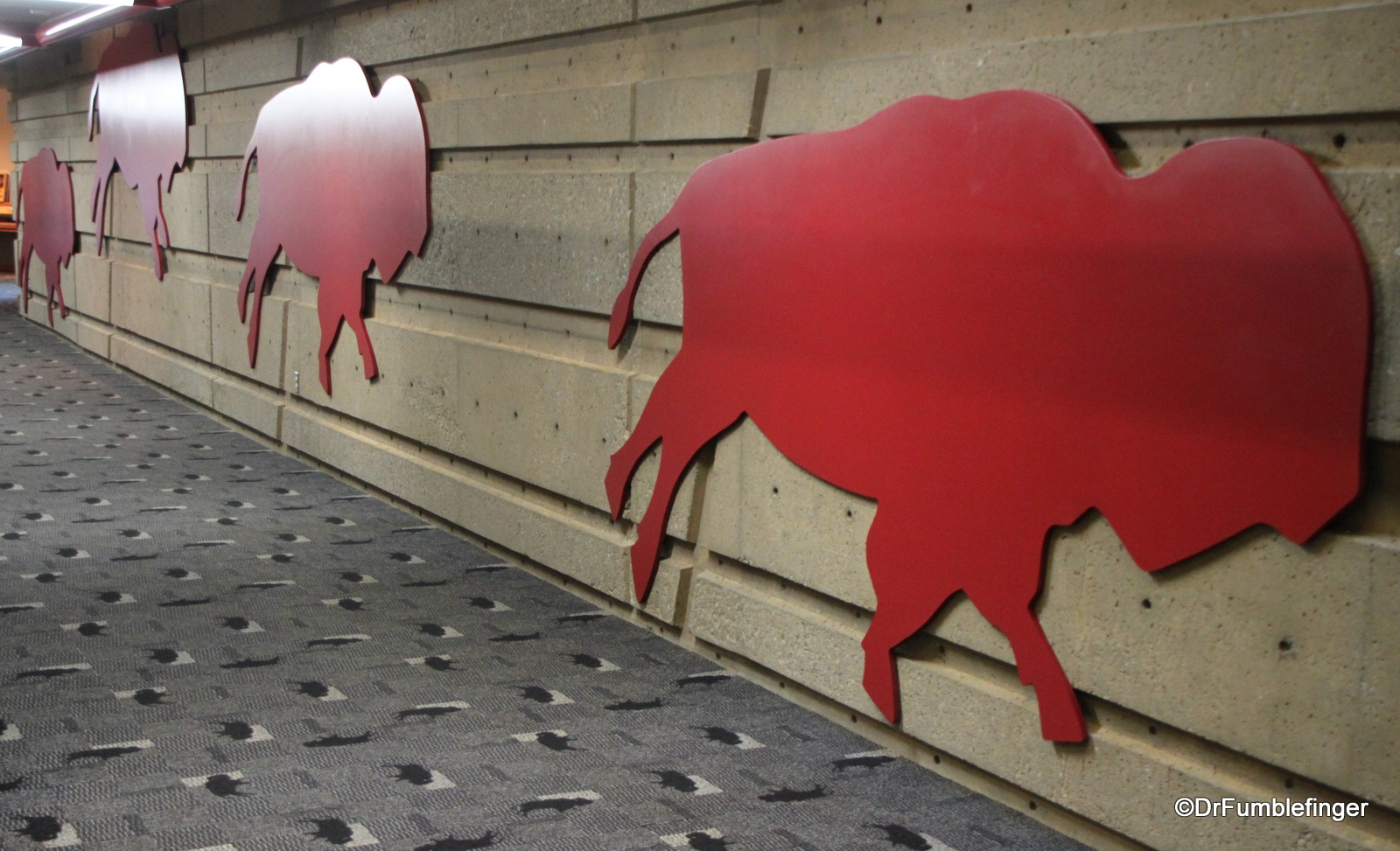

Head-Smashed-In Visitor Center

Head-Smashed-In sits on the eroded Porcupine Hills which adjoin, but are not part of, the Rocky Mountains. There are many natural springs in the area and the water and grass attracted massive herds of buffalo, as well as elk and pronghorn antelope. The variable erosion of limestone produced escarpments such as that of Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump used by the Indians for the collecting and preparing of their winter food. The Plains Indians were highly dependent on the buffalo for their existence and there was no easier way for them to stock up for the winter than at a Jump site.

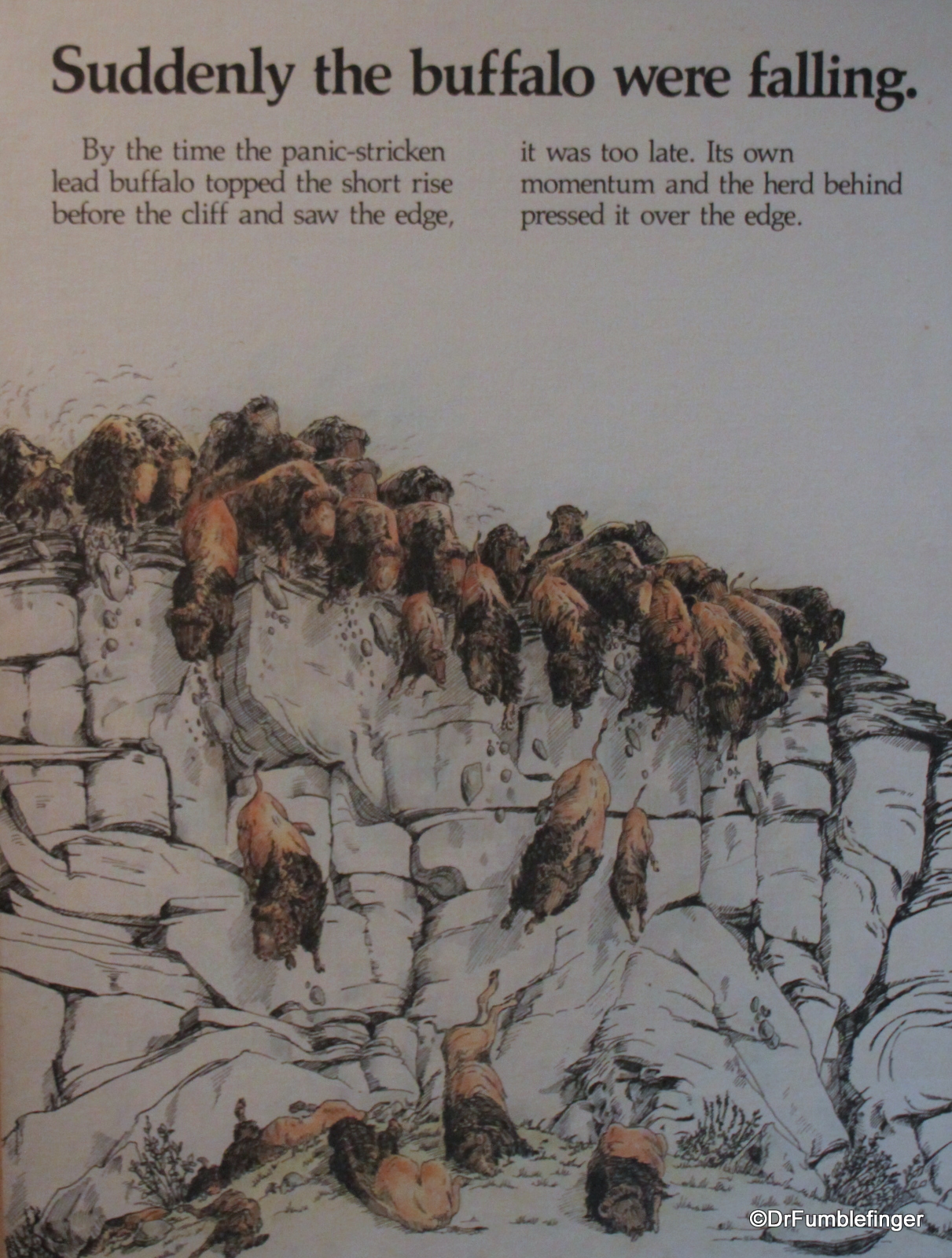

American Bison (also known as buffalo — but very different from buffalo in Asia or Africa) are a herd animal, although adult males mostly live a solitary existence. Buffalo have poor eyesight but a keen sense of smell and a strong fear of predators and prairie fires. When frightened, buffalo run in the opposite direction. Herds tend to move in an harmonious manner following their leaders. Only a few animals in the lead can actually see where the herd is running, the rest following blindly. Those few animals at the front who might have seen the jump were not able to stop because the charging herd behind them propelled them over the cliff’s edge. Due to their understanding of topography and bison behavior, native people from hundreds of kilometers around gathered here in the fall to collectively hunt the buffalo. Their intent was to make the bison “jump” (not a natural bison behavior), thereby killing them by the hundreds if possible.

Porcupine Hills viewed from top of the Head-Smashed-In Visitor Center (jump site)

The bison hunt was risky for the Natives as bison are massive creatures with sharp horns. The hunt required careful planning and coordination — a tribal effort really — including:

- The proper geography. Ideally a jump which had an up-sloped edge. There are several other jump sites in the Porcupine Hills, but Head-Smashed-In is the best preserved.

- A herd of buffalo in the right place at the right time (didn’t always happen).

- A long, ever narrowing drive range, demarcated by rock cairns along which the bison would be chased towards the cliff edge. Thousands of these cairns still exist at Head-Smashed-In. It is thought that brush was placed in the cairns and used to hide hunters; brush in the cairns might also have made the buffalo think they had no choice but to run forward (towards the jump).

- Young braves, dressed with predator hides (e.g. wolf, cougar) who stealthily approached the herd then began the stampede when the herd was properly positioned.

Young hunters hiding under wolfskins began the stampede (exhibit at the Visitor Center)

- Dozens, even hundreds, of people (mostly Blackfoot Indians) were stationed at the edges of the designated runs, between the cairns, holding large robes or burning sticks to keep the stampeding herd from breaking right or left.

- Braves to kill the fallen buffalo.

- People to prepare the meat.

The carcasses were butchered in a camp set up below the cliffs. A feast of the fresh organs was held the day of the hunt and extensive drying racks to preserve thin strips of fresh meat were quickly constructed. The flatness of the land and plentiful fresh water aided in the meat harvest. The dried meat was later ground together with fat (e.g. bone marrow) and berries (e.g. chokecherries) to produce pemmican, a nutritious food source and staple in the diet of the Plains Indians. Pemmican didn’t spoil for years.

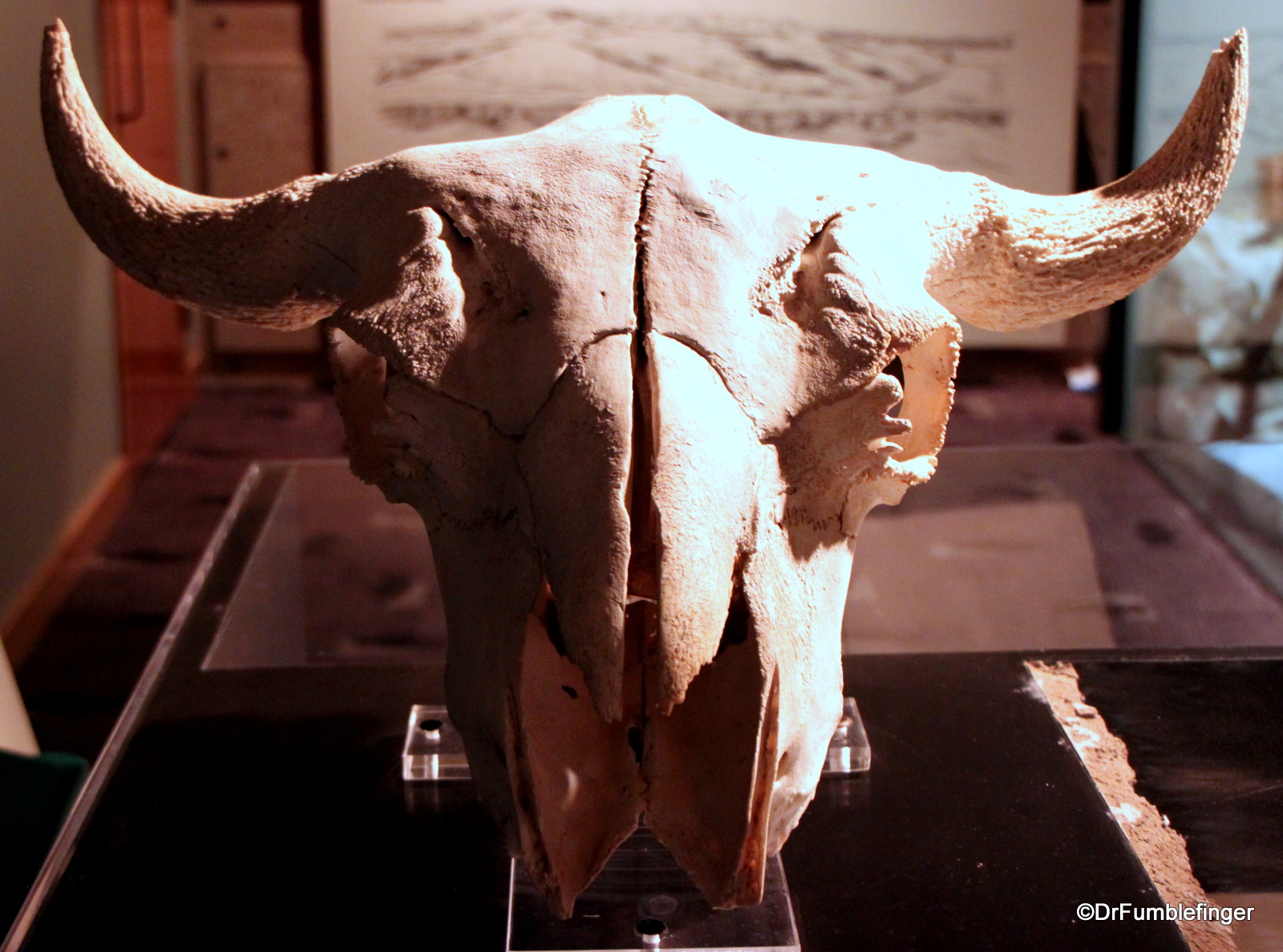

Pile of buffalo skulls at Head-Smashed-in Buffalo Jump-2012-026

Today, below the cliff kill site, are deep stratified deposits of stone rubble, broken tools, arrowheads and bones referred to as “loess”. Over thousands of years of use the “loess” here has accumulated to a depth of over eleven meters (almost 40 feet deep). Many of the buffalo jump sites were mined for their bones in the 19th century, which were ground and used as fertilizer. This didn’t happen at Head-Smashed-In. In the flat area immediately below the kill site there is also evidence of Indian encampments. Some tipi rings (stones used to anchor tipis against the wind) can still be seen.

I visited Head-Smashed-In on a day in early winter. It’s about a 2 hour drive from my home in Calgary and the winter light on the Canadian prairies was lovely — soft and diffused, as you can see on the accompanying slide show. I’d visited this site some 15 years earlier with my family when the kids were young. The hills then were green and attractive in early summer but the area was equally appealing to me in the winter time. The site is easy to visit as you make your way from Calgary to Waterton National Park or British Columbia.

(Click on thumbnails to enlarge, right arrow to advance slideshow)